Analysing Swansea City’s Most and Least Influential Attacking Players

This article was written in the first week of October, so Swansea City’s performances under Bob Bradley are not included.

Have you ever wondered which players really make a difference for your team? Football’s uneasy relationship with statistics has meant that, goalscorers aside, value can be hard to quantify. We’ve all got our favourite players, but often our affection has little to do with actual performance. What if some players aren’t as good as we like to think they are? Or if others aren’t getting their due?

Football is ultimately about scoring goals, but statistically speaking, football’s figure chasers do a horrible job of tracking which players help produce those goals, and the idea of assists is still contentious. The concept has gained more ground in the fantasy football community as it helps generate points, but could it work in ‘real’ football too?

At present, an assist in the Premier League is considered to be “A pass that directly leads to a chance scored by a teammate“. Under this system, the contribution of players who were involved earlier in the attacking play is overlooked. Even a great final pass is forgotten about if the goal scorer takes one too many touches before shooting.

Opta Stats have an entire page on their website criticising what they apparently consider to be unreasonably loose definitions for assists, but their own definition is obsessed with the intention behind passes. It shouldn’t matter that a player intended for their pass to lead to a shot on goal. What’s more interesting is being able to build a clearer picture of which players are most often involved in moves which eventually lead to goals.

A player who wins a penalty or direct free kick from which a goal is scored should be credited with an assist. An attacking player should get an assist on an own goal, as should a player whose pass or shot was unintentionally deflected into the path of the eventual goalscorer. Secondary assists should count (i.e. assists for the second to last player to be involved in a goalscoring play aside from the scorer). These players all played a part in their team scoring a goal when another player in the same circumstance might not have done, perhaps by having made different decisions with the ball.

How would things look if assists were granted in this way? What could we learn about our favourite (or least favourite) players?

Case Study : Swansea City 2015-16

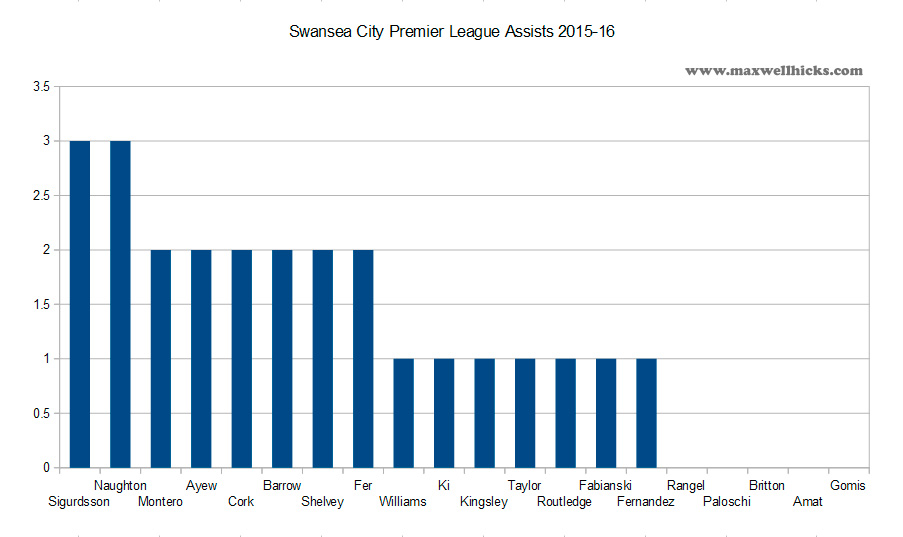

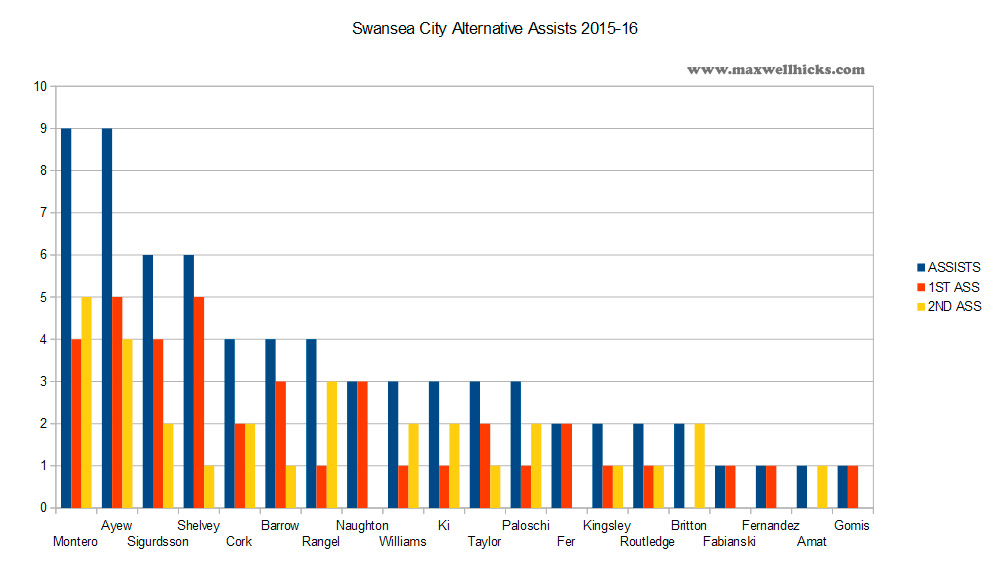

Let’s look at 2015-16’s Swansea City. Officially, the club’s players produced 25 assists between them, with Gylfi Sigurdsson and Kyle Naughton leading the way with three a piece. Using the more generous system outlined above, that figure would have been 69 total assists°, with Jefferson Montero and Andre Ayew leading the pack instead with nine each:

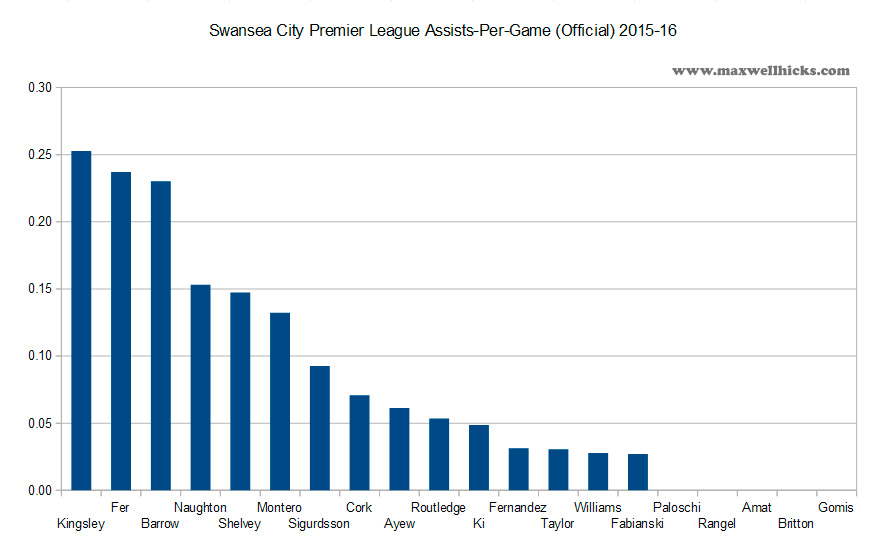

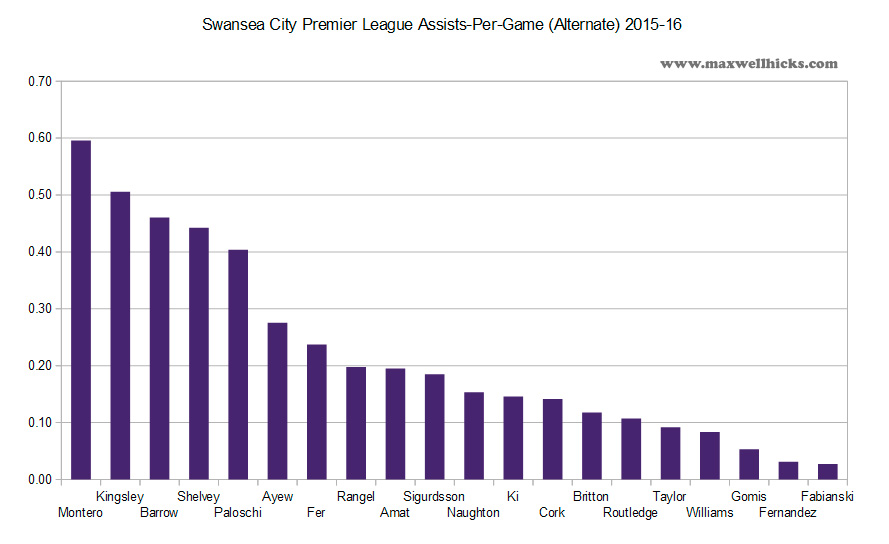

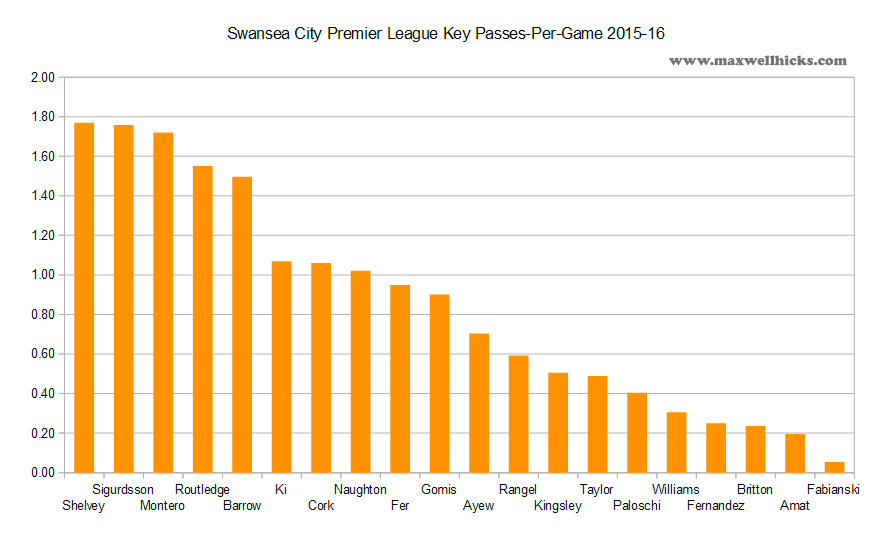

The most telling stat is the difference in assists per game, shown in the following charts. Using official statistics, Swansea’s most creative players for the 2015-16 season were Stephen Kingsley, Leroy Fer, Mo Barrow, Naughton and Jonjo Shelvey. Under the new system, the list reads Montero, Kingsley, Barrow, Shelvey and Alberto Paloschi. Three of the players are the same, but crucially Montero has leapt out of nowhere to lead the table, while Paloschi — widely (and unfairly) considered a ‘flop’ signing — quietly helped lay on more goals than he scored:

What can we learn from this? Mostly that while Montero’s crosses don’t always lead directly to a converted chance on goal, he’s clearly doing something right. A nearly even split of primary and secondary assists tells us that while he might not always be making the final pass, he is regularly involved in plays which produce goals. In other words, the Ecuadorian winger absolutely makes a positive difference to Swansea’s attack when he’s on the field.

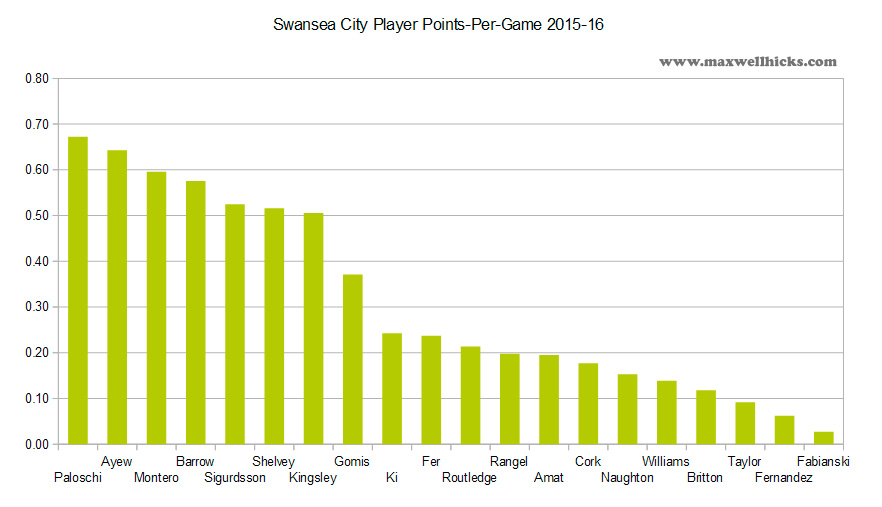

Paloschi’s case is even more surprising. His tireless running and willingness to drop deep produced 0.4 assists per game, but only under the more comprehensive system. And it gets even better for the Italian. If we add each players goals and assists together to make a points total, and then look at the points-per-game figures, we can determine which Swansea players were the most likely to make something happen:

Paloschi leads the list, ahead of more obvious candidates Ayew, Montero, Barrow and Sigurdsson. Following the logic that a player can’t get an assist without a goal being scored, assists should hold similar importance to goals. A goalscorer who achieves anywhere near 0.5 goals-per-game can be considered lethal, scoring every other match and good for around 20 Premier League goals a season. A player who chalks up a 0.5 points-per-game average instead is therefore almost as valuable. Paloschi’s 0.67 ppg suggests the Italian was far from a flop in South Wales; on the contrary, in his handful of appearances he was actually Swansea’s most dangerous player. It’s just a shame he didn’t settle.

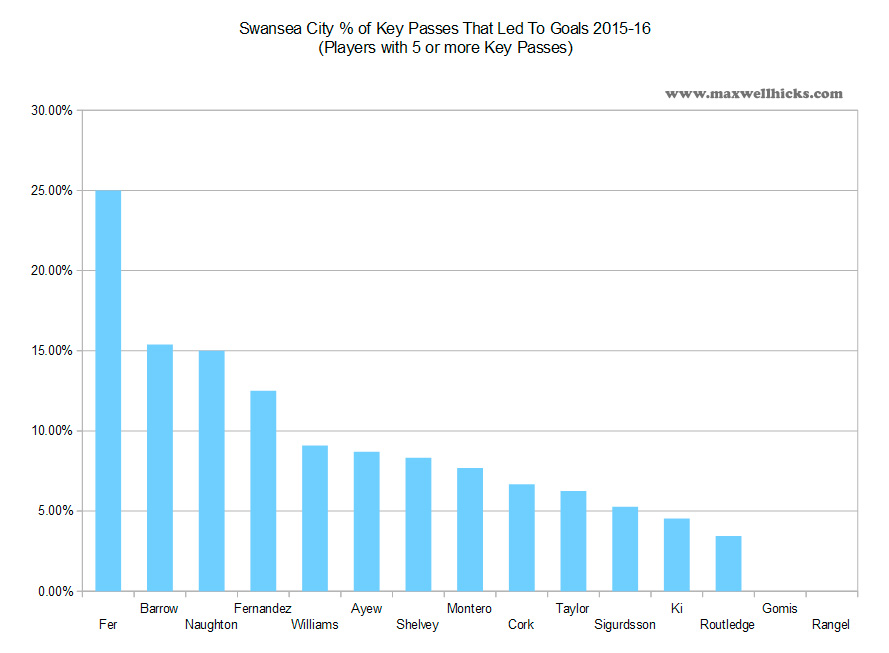

What about Swansea’s least dangerous player? Another stat can help shed some light. Key Passes are considered to be “The final pass leading to a shot at goal from a teammate“. We can’t figure out key passes under the new assists scheme without re-watching every minute of every game from last season to generate new figures. But by using the official assist and key pass statistics instead, we can still find out how often a players key passes are converted into goals, and get a rough idea of the quality of those passes:

The numbers throw up a curiosity. While most of Swansea’s attacking players have reasonable conversion figures, one in particular really doesn’t — Wayne Routledge. Routledge is actually among the teams leading suppliers of key passes (first chart), yet his passes are turned into goals far less often than those of his team mates (second chart). Sigurdsson also suffers surprisingly poor returns in this area, but at least the Icelander compensates with plenty of goals — his 11 strikes last season were good for second best on the team. Routledge however almost never scores. It took him over 100 top flight appearances to net his first Premier League goal. He’s on the field primarily to create chances yet those he does create very rarely lead to goals. Why?

The Wayne Routledge Futility Factor

The journeyman winger makes an interesting study in that he is exceptionally one-footed. Routledge often plays on the left but favours his right foot so much he’s developed arguably the best outside-of-the-boot pass in top flight football. This technique is often used to add deception by allowing the player to quickly pass or shoot at unlikely angles without changing body posture. Perhaps the same deception is too much for Swansea’s other players to read properly. Perhaps Routledge’s passes come too suddenly, too unpredictably, and his team mates simply can’t use them effectively, snatching at chances instead of preempting them.

An alternative explanation is simpler. Swansea’s most effective key passers are predominantly wide players — wingers and full backs. Despite playing as a winger, Routledge will rarely cross the ball like one, opting instead to shovel short-range lay-offs through traffic, and often from wider areas. It might just be that this approach leaves the potential goal scorer with too much to do. A conventional high cross can be simply redirected into the net, but a pass to feet in a crowded penalty area often has to be controlled and fired past a tangle of legs, a problem exacerbated by Swansea’s slow build-up play; there are always gathering defenders ready to block (the same reasoning could also explain Sigurdsson’s low return, since he nearly always plays centrally). Perhaps Routledge would fare better on a team playing at a higher tempo, where the extra space generated by playing on the break would give the shooter a better chance to convert?

The statistics examined here are all to do with attack, and none of them will say very much about Routledge’s work ethic or defensive contribution, but Swansea scored nine fewer goals (43 total) than the league average of 52 last year. Sometimes, fielding forwards because of their defensive ability is not worth the reduction in goal scoring; the game is based on scoring after all. The “total football” concept that all players should contribute to all phases of play is fine in theory, but positional specialisation still has value.

What can we learn from these figures? That for slower-tempo sides like Swansea, balls played in from wide areas are more effective than those through the middle. For example, in Swansea’s two worst performances this season so far, a 1-0 loss to Southampton and a lucky 2-2 draw against Chelsea, the team’s crosses accounted for only 4% of their total passes. In the Swans 1-0 win over Burnley and in the 2-0 loss to Hull in which Swansea were by far the better team and out-shot their opponent 23-12, that figure was 7%. It might not seem like much difference, but it is still almost double. And while Swansea no longer have Ayew or Shelvey, they will almost certainly score more goals in the future if they at least start Montero, Barrow, Kingsley and Fer — and bench Routledge.

° I calculated the assists as best I could using highlights footage. There were one or two goals where owing to lack of available footage it was impossible to determine every player involved in the build-up, so these figures are as close as I could get. They’ll suffice for this exercise.